What is the V-model?

There are three important aspects of the V-model:

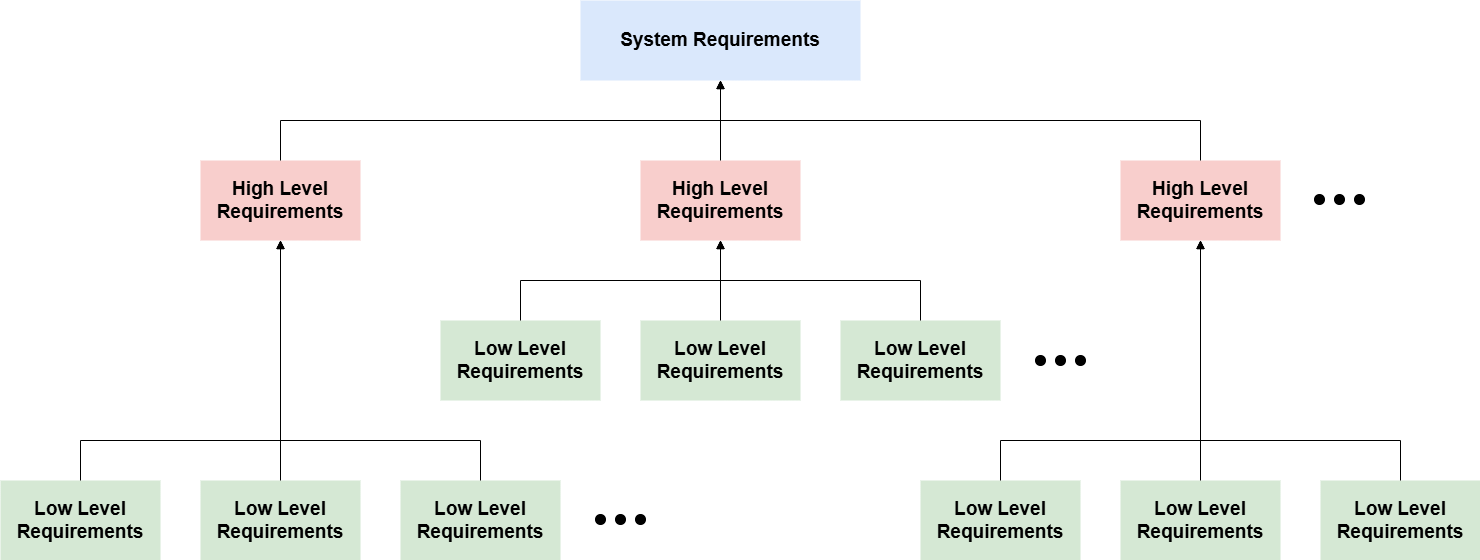

- Basically, the idea behind the V-model is that of „divide and conquer,” i.e., each system is divided into smaller subsystems until each part has a level of (requirement) complexity that allows it to be implemented. This also means that the requirements at each level should be generic enough that they can still be understood by an engineer.

- This decomposition on the left is then followed by integration on the right, where the parts of the lower level are integrated and above all, tested against the requirements of that level.

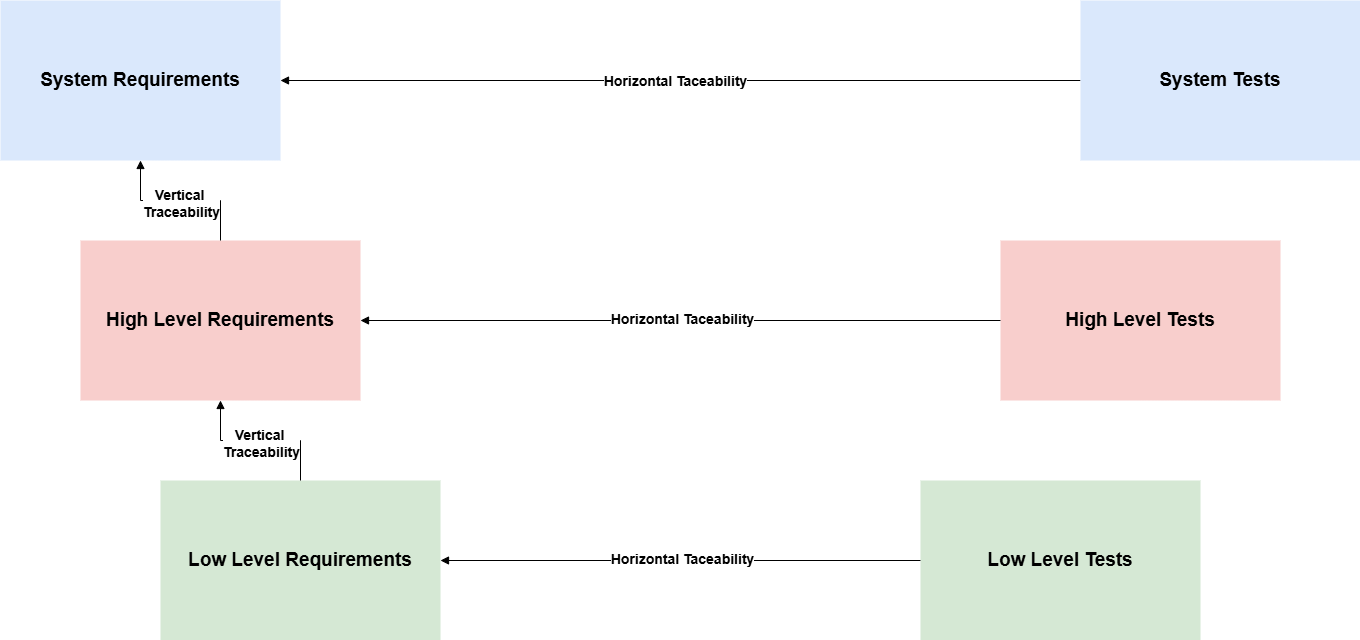

- To ensure that all requirements at one level are mapped to the next lower level, which is called vertical traceability, each requirement at my level must be covered by at least one requirement at the next lower level.

To ensure that all requirements are tested at each level, horizontal traceability is used, whereby each requirement must be covered by at least one test.

The diagram below shows three levels, which is the minimum number in most safety standards. For more complex systems, such as an entire aircraft, there may be many more.

Generic V-model (e.g., DO-178):

Where does the V-Model Come From?

The V-model has several parents; it was developed almost simultaneously and independently in the USA and Germany in the early 1980s. In the beginning, when people still believed in fixed and unchangeable specifications, it was intended as a true sequence model. In some cases, it was also mixed with stage-gate models, i.e., the next phase could only begin after the previous phase had been approved.

The problem here, of course, is that there are always feedback loops, meaning that insights gained in a later phase or changes to higher-level requirements meant that “completed” phases had to be reopened. It therefore makes more sense to view the V-model as a data management model, which makes a certain sequence more sensible, but does not strictly dictate it.

Incidentally, the V-model is also referred to as an “unfolded waterfall.” Unfortunately, this is not accurate. The „Waterfall” paper by Royce does contain graphics on the first two pages that depict the phases as a pure sequence. However, this quickly changes on the following pages, with the author even warning against a linear model...

Where is the V-Model Mainly Used?

The V-model is used in the following domains:

- Aviation, e.g. for general system design in ARP-4754, for safety in ARP-4761, and for software in DO-178

- Automotive, e.g. for general development (mainly used for software) in aSPICE

- note that this incarnation of the V-model also includes the architectures at the respective level (e.g., system architecture) in vertical traceability and also defines „tests” for this purpose

- Functional Safety, many standards prescribe the DO-178 model in principle, in some cases there are also hybrid forms with architecture documents inside the V-model

What are the Benefits of the V-Model?

- Reduced complexity: The main benefit of the V-model is „divide and conquer,” i.e., complex systems and their requirements and tests can be broken down into manageable parts.

- Document structure: In addition, the V-model leads to a clear document structure for requirements and architecture, which simplifies development and, above all, maintainability.

- Traceability: The model allows the following to be checked during development and maintenance:

- Coverage:

- whether all higher-level requirements have been implemented consistently

- whether all requirements have been tested

- whether nothing has been implemented that is not required (i.e. no incorrect assumptions have been made)

- Impact: what is the effect of a change to requirements or implementation („impact analysis”)

- Coverage:

Without the V-model, there is often no structure, or it exists only implicitly, which in large systems can lead to huge „piles” of requirements that are difficult to manage.

Overall, the V-model leads to higher upfront costs („front loading”), but lower costs towards the end of development and, above all, during maintenance.

„Divide and conquer” in the V-model (no a Gantt chart anymore):

How can the V-Model be Used Effectively?

Even though many sources (e.g. V-model in Wikipedia in general and V-Model for software development) describe it this way, it makes little sense to view the V-model as a Gantt chart or process model. It makes much more sense to view the V-model as a data management model or document structure. The link to the project management model is only loose. The sequence should be driven primarily by risk considerations: first do and try out what is associated with the greatest risks.

Of course, the V-model does specify a certain logical sequence. For example, it makes little sense to approve low-level requirements before the higher-level ones have also been approved. However, no one says that you cannot start something at another level before the higher level is „finished.”

Often the problem is not the model, but the organization. If the person in charge (quality, management, auditor...) understands the model as a pure sequence model, then it can be difficult to flexibly carry out a project without wasted effort.

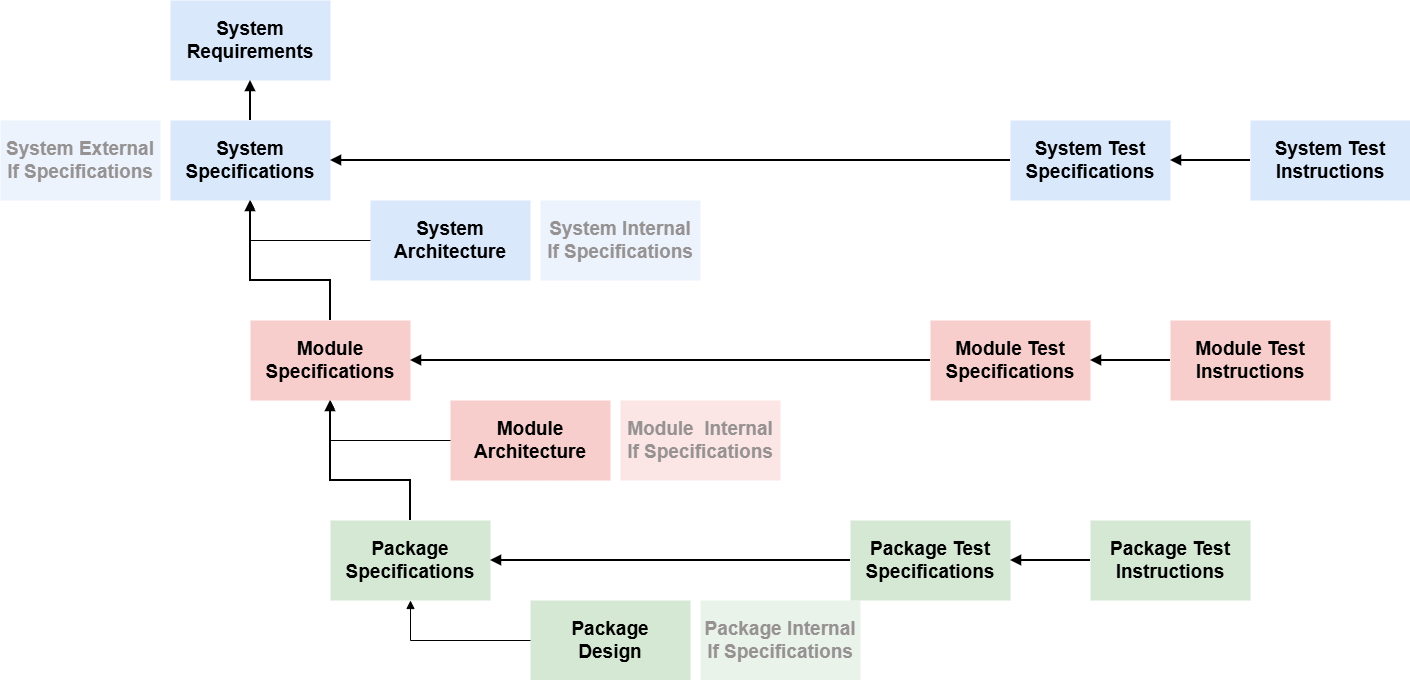

What does Solcept Implementation of the V-Model Look Like?

The V-model we use internally is mainly based on aviation. We have also included the architecture and design documents in traceability for impact analysis, but not coverage.

Interface documents are implemented separately from the architecture and specification documents at each level. This makes it easy to reference the interface requirements across the levels (otherwise, you would often have to copy the top-level interface requirements down to the lowest level, which makes no sense). This approach is possible because pure interface requirements cannot be tested without the functionality, anyway.

Tests are divided into test specifications and test instructions, the latter are the test code for automated tests.

This model can be adapted for all functional safety and security standards; for non-critical systems, unnecessary documents are omitted, typically lower levels („tailoring”).

Solcept documentation model (simplified, especially traceability):

No Comments